In the constitution of this small, banana republic was a forgotten section that provided for the maintenance of a navy.

O. Henry, “The Admiral” (147)

The unremarkable sentence above, which appeared in O. Henry’s 1904 collection Cabbages and Kings, constitutes the first use of the term “banana republic” to refer to a Latin American nation under the sway of U.S.-based fruit companies. O. Henry based the “banana republic” in question, called “Anchuria” in the book, on his experiences in Honduras. Ever since, “banana republic” has carried connotations of corruption, mismanagement, and imperial meddling. The United Fruit Company was foremost among the corporations engaged in the economic imperialism that created banana republics. A 1950 poem by Pablo Neruda, “United Fruit Co.,” suggests how some perceived the company: “It re-baptized the lands/ ‘Banana Republics’/ and on the sleeping dead…it alienated free wills,/ gave crowns of Caesar as gifts,/ unsheathed jealousy, attracted/ the dictatorship of the flies” (95). That reputation, and the “exoticness” of the banana as a relative newcomer in the American diet, were obstacles which the United Fruit Company was highly conscious of. The Burns Library holds a number of works printed by the United Fruit Company. As part of the Williams Ethnological Collection, the United Fruit Company pamphlets and tracts were once part of the personal library of Joseph J. Williams, SJ, These texts afford a view into how the United Fruit Company wished to present itself to the world.

In order to sell more bananas, the United Fruit Company first had to persuade people to eat more bananas. A good deal of research seems to have gone into this effort. A four-page pamphlet titled Bibliography on the Food Value of the Banana, compiled by the company’s Research Department in 1930, contains nothing but a list of 51 sources, suggesting that it was intended for internal, rather than public, use. The bibliography

includes such scientific articles of apparent significance as P. Rohmer’s “The Stimulating Action of Vitamin C on Certain Forms of Chronic Indigestion in Infancy” and J.J. McNamara’s “Lowell Fights Undernourishment Among Its School Children”. A simple browse through the bibliography’s titles suggests that the company was interested in the potential of the banana to combat medical conditions including nephritis, scurvy, constipation, and especially celiac disease. No fewer than nine of the 51 items in the bibliography include the word “celiac” in their titles. (In fact, bananas were considered a miracle cure for symptoms of celiac, with doctors sometimes prescribing children to eat as many as 200 bananas per week. Bananas were, in fact, so good at masking its symptoms that this practice contributed to a widespread tendency to under-diagnose the disease [Neimark 2017].)

Other documents were more clearly intended for mass distribution. A sense for the tone of this banana propaganda may be gleaned from Bananas: A Food Children Need:

Like the Good Fairy at the Royal Christening, Mother Nature bestowed a precious gift on childhood when she fashioned the banana. Thinking to create a food both nutritious and delightful to taste, she combined in its tender pulp all the sustenance of a vegetable and the sweet succulence of a fruit. Then with golden sunshine for her color scheme, she sealed it safe from dust and dirt in a germ-proof packaging. (2)

This pamphlet consists of 24 pages of nutritional banana facts, banana recipes, and expert medical opinions on bananas, aimed toward children and the parents responsible for feeding them. Another pamphlet, The New Banana, affords not only 63 recipes for those wishing to eat bananas literally morning, noon, and night, but fun “banana news,” as well – including the tale of “a young Norwegian” who (purportedly) walked the 250 miles from Olso to Christianssand entirely on a diet of bananas and milk (United Fruit Company 1931).

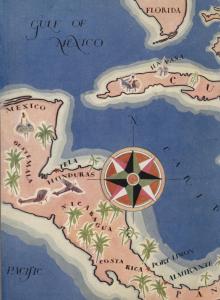

A small map on the inside cover of The New Banana shows the area of the United Fruit Company’s operations in Central America.

The increasing popularity of the banana among American consumers meant a great deal of work for the company – not just in the direct growing and harvesting of bananas, but in building infrastructure and communities for its employees, as well. A publicity brochure for the company, United Fruit Company: Nature and Scope of its Activities claims that tropical diseases made the 3,482,042 acres owned or leased by the company unworkable prior to the company’s intervention, which “transformed the zone of its tropical operation into modern sanitary and healthful communities” (United Fruit Company 1931, 6). Its 80,000 employees “maintain[ed] water works, electric light and ice plants, laundries and bakeries… churches, schools, baseball grounds, tennis courts, golf courses and swimming pools” (United Fruit Company 1931, 7). These amenities, the brochure stresses, were for both American and local employees, and the greater communities at large. Perhaps out of sensitivity to a widespread perception of the company as an overbearing imperialist power, the brochure emphasizes corporate policies geared toward making its employees decent and respectful guests:

It is the fixed policy of the United Fruit Company that its officials and employees in thetropics speak the Spanish language, and that while those who are not citizens refrain from all political activities and affiliations, yet they must support all that is best in the social and cultural life of the countries in which they work. (United Fruit Company 1931, 7)

Sensitivity to the company’s image as an overbearing imperial power seems to inform much of the company’s messaging. In a speech given to Institute of Politics in 1925 (published in a collection of Cutter’s speeches under the title Trade Relations with Latin America), United Fruit Company president Victor M. Cutter attempts to head off such characterizations at the outset:

I hold no brief for imperialism and deprecate any slightest imperialistic tendency on the part of the United States towards Latin America. I have, however, no patience with theorists who hold that commercial relations do not bring closer understanding between people… Cultural and intellectual harmony between nations has invariably followed commercial and industrial relationships which have enabled them to acquire the physical comforts and mechanical devices which give leisure for cultural and intellectual pursuits. (Cutter 1929, 5)

The idea that international trade would foster a flourishing of international peace, understanding, and mutual prosperity is an old one; former slave and memoirist Olaudah Equiano ends his 1789 Interesting Narrative by recommending the same program for Britain’s relationship with Africa, for example. Cutter returns to this theme

at numerous points in his address, and even positions himself as an emissary for Americans’ understanding of Central America: “Nearly all Americans,” Cutter says, “have a very badly exaggerated impression of unstable political conditions, and an almost total lack of appreciation of the ancient art and culture to be found in the Central American cities” (48). In Cutter’s account, and in those of his company’s publications, the United Fruit Company functions as a benevolent entity respectfully bringing industry and infrastructure to a disadvantaged but proud region’s people.

Was this the case? Pablo Neruda clearly didn’t believe it was, and history supply evidence for his view of the company as a meddling imperial presence. The United Fruit Company’s literature for public consumption neglects, for example, to mention the 1928 Banana Massacre, when Colombian soldiers murdered a number (somewhere between 47 and 2000, depending on whether one believes the army’s account or local folk history) of striking United Fruit Company workers. Although the company’s direct involvement with the massacre has never been proven, it’s willingness to cooperate with the Colombian government before and after it contributed to the company’s reputation for repressive activities and support for despotism (Bucheli 2005, 183). That reputation may go some way to explaining why the company pursued such an aggressive propaganda campaign beginning just a few years later. Whether the company was ultimately a force for the development or the exploitation of Latin America may still be open to debate, but scholars wishing to investigate the company’s side of the argument are welcome to do so at our library.

- Eric Pencek, Boston College PhD Candidate (Reading Room Assistant), John J. Burns Library

Works Consulted:

- Bucheli, Marcelo. Bananas and Business: The United Fruit Company in Columbia, 1899-2000. New York: NYU Press, 2005.

- Cutter, Victor Macomber. Trade Relations with Latin America. Boston: United Fruit Company, 1929.

- Henry, O. “The Admiral.” In Cabbages and Kings. New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1904.

- Neimark, Jill. “Doctors Once Thought Bananas Cured Celiac Disease. They Saved Kids’ Lives – At a Cost.” National Public Radio, Incorporated online, last modified May 24, 2017. https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/05/24/529527564/doctors-once-thought-bananas-cured-celiac-disease-it-saved-kids-lives-at-a-cost

- Neruda, Pablo. The Essential Neruda: Selected Poems. Edited by Mark Eisner. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2004.

- United Fruit Company. The New Banana. Boston: United Fruit Company, 1931.

- —. Jamaica Via the Great White Fleet. Boston: United Fruit Company, 1913.

- United Fruit Company Educational Department. Bananas: A Food Children Need. Boston: United Fruit Company, 1930 (?).

- United Fruit Company Publicity Department. United Fruit Company: Nature and Scope of Its Activities. Boston (?): s.n., 1931.

- United Fruit Company Research Department. Bibliography on the Food Value of the Banana. Boston: United Fruit Company, 1930.

- —. The Food Value of the Banana: A Compilation from Recognized Authorities. Boston: United Fruit Company, 1929.

Leave a comment