Black History Month has been celebrated during the month of February since its precursor—Carter G. Woodson’s Negro History Week—was first observed in 1926. Black History Month provides an opportunity to commemorate the various contributions of black Americans to the history and culture of the United States, but this tribute should extend throughout the calendar year rather than be confined to a single twenty-eight day period.

Although the Burns Library is best known for its collections relating to Irish studies, Jesuitica, Catholic liturgy and life in America, and Boston history, the library’s expansive holdings include many materials outside of these topics. In efforts to extend the spirit of Black History Month, this post highlights a less prominent portion of the Burns collection: the works of black American writers such as Phillis Wheatley, Countee Cullen, and Richard Wright. These writers were essential contributors to the American literary canon and their texts help illuminate not just African American history, but American history more broadly from the antebellum period through the twentieth century.

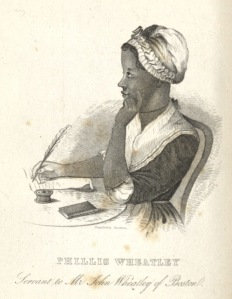

In 1761, Phillis Wheatley endured the Middle Passage of the transatlantic slave trade and arrived in colonial Massachusetts, where she was purchased by Boston merchant John Wheatley as a ladies maid for his wife. Phillis learned to read and write from the Wheatleys’ daughter Mary and soon demonstrated an “uncommon intelligence” and a proclivity for poetry. In 1773, with the publication of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, Phillis Wheatley became the first published African American woman.

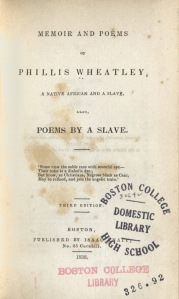

Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and a Slave was originally published in Boston in 1834. In the Burns Library’s Boston Collection is a copy of this text’s third edition, published in 1838, which contains the full text of Wheatley’s 1773 anthology in addition to extensive biographical information provided by Margaretta Matilda Odell, “a collateral descendant of Mrs. Wheatley.” Odell’s account is the only comprehensive documentation of Wheatley’s life, continuing to serve as the primary source of biographical material for modern biographers of Wheatley. Odell chronicles the life of Wheatley, describing her girlhood in Boston, travels in London, emancipation, marriage, motherhood, decline into poverty, and ultimate death at the age of thirty-one.

In response to tempered praise of Wheatley as talented, but “a solitary instance of African genius,” Odell insisted that other enslaved individuals would have undoubtedly demonstrated similar intelligence had they, like Phillis Wheatley, fallen into “generous and affectionate hands.” According to Odell, slavery fettered both the bodies and minds of the individuals in its grip. “How then can it be known,” Odell implored, “how often the light of genius is quenched in suffering and death?”

Interestingly, Odell’s anthology also contains the works of George Moses Horton, who became the first black poet published in the American South in 1829. His first book of poems, entitled The Hope of Liberty, was published while he was still a slave in Chatham County, North Carolina. In combining the work of Wheatley and Horton, Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and a Slave, represents two of the three black American authors (the third is Jupiter Hammon) who were published while still enslaved.

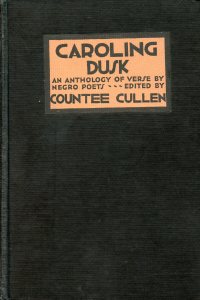

Born in 1903, poet Countee Cullen was raised in Harlem, New York City. After attending high school in the Bronx, Cullen entered New York University, where his work enjoyed wide publication and received numerous awards. In 1925, Cullen matriculated at Harvard University to pursue a masters degree in English. In the same year, Cullen’s poetry was first anthologized in a collection entitled Color. Countee Cullen was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance—the 1920s cultural movement that produced an outpouring of African American art, literature, music, and cultural expression. His poetry was nationally known, he received more literary awards than any other black writer in the 1920s, and he received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1928.

The Burns Library has a first edition copy of Countee Cullen’s Caroling Dusk: An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets. Published in 1927 by Harper and Brothers, Caroling Dusk collectively presents the poetry of many prominent and lesser-known black poets of the Harlem Renaissance era, including Langston Hughes, Anne Spencer, Claude McKay, Gwendolyn Bennett, James Weldon Johnson, Mary Effie Lee Newsome, Georgia Douglas Johnson, and Countee Cullen himself. The book also includes decorations by black artist Aaron Douglas, another famous figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

The purpose of Caroling Dusk, as Cullen explained in the foreword, was to make more widely available the collected works of black poets gaining popularity during the Harlem Renaissance. Although Cullen was committed to publicizing the work of black poets, he was insistent that the art of poetry transcended racial difference. In the text’s foreword, Cullen explained his reasons for subtitling his anthology “An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets” rather than “An Anthology of Negro Verse.” According to Cullen, skin color was the only factor distinguishing black poets from white poets in the early twentieth century. “This country’s Negro writers may here and there turn some singular facet toward the literary sun,” Cullen wrote, “but in the main, since theirs is also the heritage of the English language, their work will not present any serious aberration from the poetic tendencies of their times.” Cullen believed that black poets were fundamentally American poets and that any distinction between the two was “needless.”

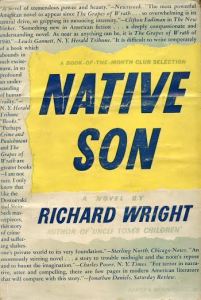

Richard Wright was one of the most widely acclaimed black writers of the twentieth century. Born in 1908 in Mississippi, Wright left the Jim Crow South for Chicago in 1927, where he joined the Communist Party and began developing his writing craft. In 1937, Wright moved to New York. Wright came to national attention after the publication of his short story collection Uncle Tom’s Children in 1938, which also earned him a 1939 Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1940, Wright published the novel Native Son, followed by Black Boy in 1945. In 1946, disillusioned by the racial climate of the United States, Wright moved to Paris and became a permanent American expatriate. He continued to write extensively until his death in 1960.

The Burns Library possesses a first edition of Wright’s Native Son. The book retains its original dust jacket and was originally owned—as evidenced by an extant bookplate—by Gertrude M. Dagnino of Wakefield, MA. The novel is illustrative of the themes of race, violence, and class that emerge throughout Richard Wright’s work. Native Son follows the character of Bigger Thomas, a black nineteen year old living in Chicago’s South Side who commits two murders and is put on trial for his life. In Native Son, Wright sought to demonstrate the systemic societal, economic, and political forces behind black crime and poverty. The novel was a best-seller, and was the first book written by a black American author selected by the Book of the Month Club. Despite its popularity, Native Son drew criticism—most notably from James Baldwin—for its stereotypical depiction of a brutish black male. The popularity and controversy surrounding Native Son is a testament to the novel’s significance within American history and the American literary canon.

In addition to possessing great literary merit, these three texts guide readers through several of the most significant moments in American history: slavery, the Harlem Renaissance, and the tense racial climate of mid-twentieth century US. The works of Phillis Wheatley, Countee Cullen, and Richard Wright therefore underscore the literary and historical significance of black writers to a broader understanding of American cultural history. Their work should be read, discussed, and appreciated throughout the year, not only in February.

If you would like to learn more about these books, contact the Burns Library Reading Room at 617-552-4861 or burnsref@bc.edu. For more information on African American Literature, read BC Librarian Brendan Rapple’s African American Literature Guide and the American Antiquarian Society’s African American History Resources page.

- Grace West, Burns Library Reading Room Student Assistant & BC’15

Leave a comment